Disruptive Southwest Trends

When the FCSFP began, an array of negative trends was identified as strongly impacting the well being of the region:

-

|

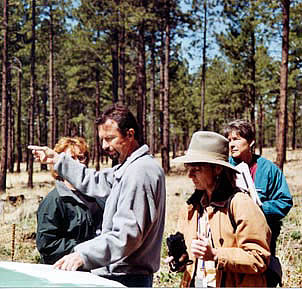

Faces of community forestry in the Four Corners region—Steve Gatewood, Greater Flagstaff Forests Partnership executive director (pointing), Kathryn Mutz, Univ. of Colorado Law Center (background) and field-tour participants. |

Unhealthy Forests: Hundreds of thousands of acres of unhealthy, overstocked forests, resulted from myriad conditions, including exclusion of natural fire for a century. This vast forest ecosystem extends over much of what is known as the Colorado Plateau and the northern highlands of the Rio Grande Valley .

- Polarization: Communities and public interest groups were extremely polarized over which resource management solutions were appropriate for use in these forests. These disputes were being negotiated in courts, rather than in local community contexts, while these same communities were being socially and economically fragmented.

- Mill Closures: Many timber mills had closed, undermining the already tenuous stability of forest-dependent communities. In most cases the mill closures created unemployment among several hundred workers in highly forest-dependent economies, where no replacement jobs were available. However, a few small- and medium-sized, often family owned, wood-processing businesses were able to survive the severe economic changes.

- Market Disruptions: Markets for forest products became increasingly disrupted, with large gaps in processing and transportation infrastructure, a lack of modern equipment, and with little or no investment in new conservation knowledge, skills, and tools. Surviving small businesses were ill prepared to make needed capital investments and changes in technology, with many of their owner-operators nearing retirement.

- Organization/Legal Gridlock: Public land managers were in a continual state of organizational and legal gridlock, unable to take very basic steps to improve ecosystem conditions. In time, as significant reductions in timber production programs on USFS lands, major reductions in staff occurred, leaving little or no capacity for resource monitoring, evaluation, or conservation in ecosystems that were in an increasing state of decline.

- Social Change/Policy Conflict: Resentment grew between community leaders, forest-product workers, resource managers, and environmental advocates who had grown weary of the inability of traditional, formal systems or institutions to address the restoration needs of stagnant natural landscapes where natural fire had been excluded. By and large, the degree of social change and public policy conflict had created an atmosphere where people were not talking or working together to achieve sustainable ecological improvements.

These trends created a context where the need for systemic change in the social, economic, and ecological approaches to forest improvement became increasingly clear. The specific lack of concerted action that was needed to rebuild significant and sustainable forest stewardship was no longer a viable option. For many community leaders, local business owners, and foresters hamstrung by legal gridlock, an ecological crisis existed.

t |